The plot concerns a young, weak-willed theology student, Shiro, his amoral doppelganger Tamura, and the web of sin they draw everyone around them into. Strong enough for two remakes, the movie is sometimes also known as The Sinners of Hell, although the straight-up translation would be simply, Hell. So you probably won't be surprised where all the main characters end up for the last third of the film. You'll know whether or not you're hooked when this man appears and proclaims "I am King Enma of Hell, I am Lord of the Eight Hells of Fire, and I am Lord of The Eight Hells of Ice. Hear me! You who in life piled sin upon sin will be trapped in Hell forever. Suffer! Suffer! The vortex of torment will whirl for all eternity!" Don't worry, that vortex ain't a metaphor.

The lead-up to Hell does indeed feature an impressive amount of sin: hit and run accidents, drunkenness, promiscuity, secret paternity of children, pre-marital sex, soldiers stealing water from dying comrades, sensationalist reporters driving men to suicide, penny-pinching doctors serving spoiled fish to old people, revenge murder, poison sake, and mass suicide. Japanese Limbo even makes a cameo appearance, and has very strict rules; in Christian tradition, Limbo is reserved for unbaptized babies, but here, Limbo is for children who die before their parents. Wow, that must be crowded. Think of all the soldiers, or anyone else for that matter, that die before their parents. And think of all the parents that live forever! John McCain and Rupert Murdoch could both still die before their mothers.

Director Nobuo Nakagawa and writer Ichiro Miyagawa present Hell not as a literal place of confinement, but as an abstract state of being; endless tortures transition randomly, surrounded by total darkness and the eternal screams of loved ones, in a barren, inexplicable landscape that transforms constantly. No pitchforks, but there is a pit of fire, in addition to the aforementioned vortex of torment, as well as fields of giant glass shards, fields of stones, fields of arms, fields of feet, freezing rivers, boiling rivers of blood and mud, ghostly bone-armored soldiers who administer club beatings, hysterical circle running, flame broiling, brains gouged through ears, stabbing, sawing, dismemberment, flaying, eye-plucking, beheading, and a particularly cruel punishment where one must struggle endlessly to save their unborn children from a spinning wheel of fire. Holy shit, this was 1960?

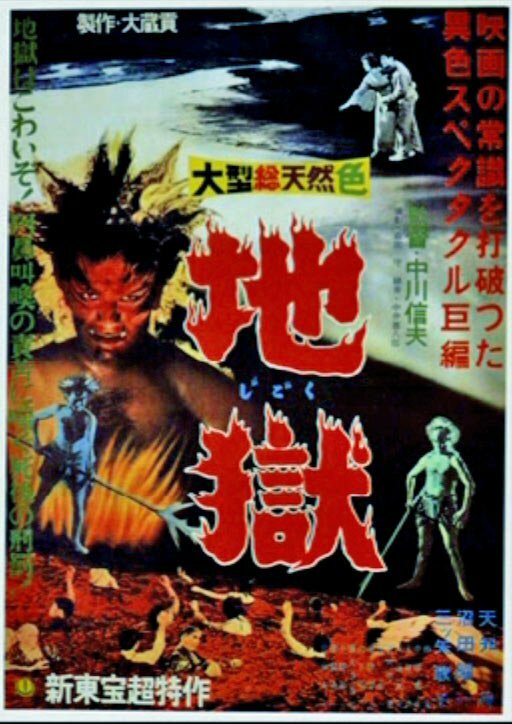

The pre-Hell sequences may seem a little silly, with the broad, sometimes campy, theatrical acting style and the portentous and confusing omens of death and sin. A clock stopped at 9pm doesn't mean much to a Western audience, but in Japanese the number 9 is a homophone for suffering, and is considered such bad luck that people generally pronounce it differently in polite conversation. But the payoff in Hell is worth any minor quibbles. As the last film produced by Shintoho studios, they really went the extra mile to render an effectively nightmarish Hellscape, even when cash-concerns forced them to have actors dig their own pits in the Hell scenes.

This film belongs to a sub-genre in Japanese art known as Ero Guro Nansensu which roughly and actually kinda obvious translates as Erotic-Grotesque-Nonsense. Can't help but think American genres seem a little boring when compared to that. The genre name itself inspires the very feelings that its named for! People clamored for years to see this film when it was all but unavailable outside of Japan after its release, but thankfully we know live in the age of home media and can easily and comfortable enjoy this film with very little trouble. As terrifying or ridiculous as the film may sound, it ends with a purifying vision of heaven, a palette cleanser, that signals the deeper intentions of the film-makers to make more than just a morality play or a freak show, despite warning the viewers that "those who sign their conscience over to the devil" will enjoy the same fate as the assorted, sordid characters depicted.

No comments:

Post a Comment